Blog

Flipped your noodle? You definitely DON’T need more self-control

- October 2, 2025

- Posted by: Jouré Rustemeyer

- Category: Self-control

We often hear the message that children and adults just need to learn more self-control. We need self-control when we are tired, stressed, overworked, frustrated, irritated, overwhelmed or basically to deny every single emotion except self-control. Whether it’s sitting still in class or a meeting, managing frustration, or “behaving better” at home — self-control is treated like the magic solution to anything that makes anything and everything better. I am here to tell you: you definitely DON’T need more self-control!

Why? Because self-control isn’t something you can just switch on. It isn’t a lever situated conveniently on your shoulder or butt that you can choose to flip or not, especially when the stress load is too high.

And this is where we need to pause and ask: are we focusing on the right thing?

What we usually mean by “self-control”

When we talk about self-control, we usually mean being able to regulate emotions, resist impulses, and manage behaviour. Schools, workplaces, and even therapies often put a lot of effort into teaching these skills.

And yes, they can be useful. But here’s the catch: self-control takes brain power. And brain power is the first thing that disappears when we’re overloaded.

It rarely helps to tell someone to “calm down.” In fact, those words usually have the opposite effect. When I’m stressed or anxious and someone says it to me, it feels muffled and distorted, almost patronising. Instead of soothing me, it only makes me flip my noodles even more!

Still not convinced? Research has proven that when a child is in the middle of a tantrum, their emotional brain — the limbic system — takes over. The part of the brain that supports reasoning and self-control, the prefrontal cortex, is far less active. In other words, their actual capacity for self-control is reduced.

The same thing happens to adults. Think about a time you were already stretched to your limit — maybe a tight deadline, constant interruptions, and then a sudden crisis thrown on top. In that moment, it’s much harder to stay calm, make thoughtful decisions, or resist snapping back. Your stress load has pushed your brain into survival mode, and your ability to self-regulate is temporarily diminished.

Stress load is the build-up of all the things our nervous system is juggling — sensory overwhelm, social pressure, noise, unpredictability, fatigue.

Think of it this way: if you’re already running on empty, the tiniest extra demand can tip you over the edge. That’s not a “lack of self-control.” That’s a body and brain saying, “I can’t take on one more thing.”

Self-control won’t “unsink” you

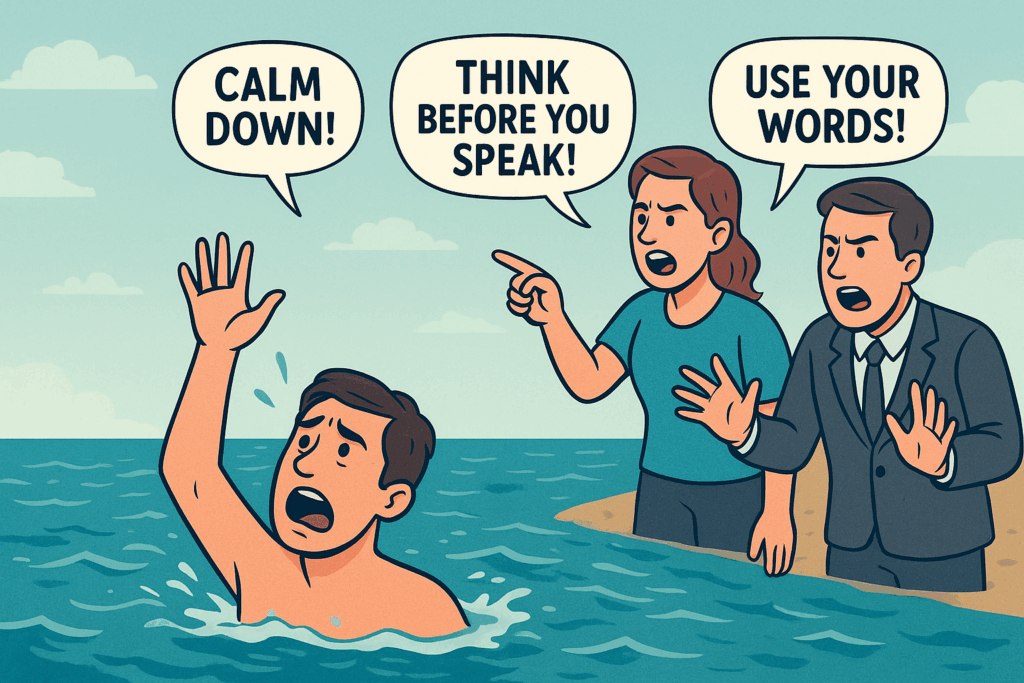

When someone is drowning in stress, their capacity for self-control is reduced — sometimes almost completely. It’s like being caught in a storm at sea. In that moment, they can’t swim smoothly, pace their strokes, or think about technique. Survival instincts have taken over.

If you saw someone panicking in the water, you wouldn’t stand at the edge shouting, “Calm down! Think clearly! Control yourself!” You’d throw them a life raft. Because in the middle of panic, the brain simply doesn’t have access to its higher reasoning or self-regulation systems.

It’s the same for children in the middle of a tantrum, or adults who are overwhelmed by stress. Self-control isn’t a choice they’re refusing to make — it’s a capacity they temporarily don’t have. That’s why the most effective response is to reduce the stress load first, and then, once calm has returned, the ability to regulate naturally comes back online.

Why reducing stress load matters matters more than increasing self-control

When we lower stress — by making environments calmer, reducing unnecessary demands, providing sensory supports, or creating predictable routines — we free up the brain’s capacity to regulate itself.

Think of it this way: I am old enough to remember that a computer had to be regularly restarted otherwise its RAM was “too full” and it got slower and slower, and eventually crashed. That was because it never had a chance to “relax” and clear its capacity to function at optimal levels.

Another way to think of it is to imagine a beautiful Dior bag, one of those “clutchy” numbers, and instead of putting just enough in, we stuff more and more things into it, never taking anything out first. Pretty soon it is going to come apart at the seams, and then later break entirely.

We need to take stress “out” of our minds, wipe the slate a bit before we just write over what is already written on it. We need to reboot, reset and RELAX. This is the skill we really need to learn.

If we learn how to relax and reset, suddenly, the very behaviours we were trying to “control” become more possible, because the system isn’t overloaded anymore.

And yes, self-control still has a place

This isn’t to say that strategies for regulation aren’t useful, and this is not a post to say that they are useless, not at all. In fact, we have an entire course regarding Executive Functions which is a core facet of self-control jam packed with practical strategies and advice.

Naming emotions, recognising triggers, planning ahead, taking deep breaths, grounding exercises, or using visual cues can all help a person regain control. Even simple actions, like pausing before responding, asking for a short break, or having a quiet, predictable space to reset, give the nervous system a chance to settle.

But the key point is that these strategies only work if the brain actually has the capacity to use them. When stress levels are too high, the parts of the brain responsible for self-control are overwhelmed, and no strategy — however well-practiced — can fully override that.

Self-control through a neurodiversity lens

For autistic individuals, ADHDers, and others who experience the world differently, this point is even more critical. Behaviour that looks like “defiance” or “lack of discipline” is often not a matter of choice — it’s a sign that their system is overloaded, that their brain’s capacity for self-control has been exceeded.

The reason this might “seem” to happen more often with neurodivergent individuals is NOT because they are weaker in some ways. It is because they find the environment more challenging, and more aspects of the world in general is more demanding on a lot of levels. Think if you can work and function properly in a setting where you are blasted with million watt lights. How long do you think you will last before your capacity for self-control is completely diminished?

Shift your thinking

If we shift our thinking from asking, “Why can’t they control themselves?” to “What’s pushing them beyond their capacity?”, we create far more effective and compassionate support. We also open the door to building resilience over time. Resilience — the ability to handle stress without becoming overwhelmed — can absolutely be taught and strengthened through strategies, practice, and supportive environments.

The important thing to remember is that this is a slow process. Capacity for self-regulation doesn’t magically increase overnight; nor does it grow under stress. It grows gradually, as the brain and nervous system learn that they can manage challenges safely. Expecting instant change is unrealistic, but with patience, consistent support, and reduced stress loads, a person’s ability to tolerate and recover from stressful situations can steadily improve.

The takeaway

Reducing stress load isn’t the opposite of self-control — it’s the essential first step. When the brain is overloaded, self-control simply isn’t available, no matter how much willpower or skill someone might have. But once the storm calms, the nervous system resets and the space for regulation reappears. That’s when the strategies we value — pausing, naming emotions, planning ahead, using calming techniques — can actually take root and work.

So maybe the better question isn’t “How do I have better self- control?” but “What can I do to make life less overwhelming so control becomes possible?” Because self-control isn’t about sheer force or endless practice in the middle of chaos — it’s about building the right conditions. By lightening the stress load, we make it possible for self-control to emerge naturally, and from there, it has a chance to grow stronger over time.