Blog

How To Stop Decision Fatigue And Its Effects On Neurodivergence

- June 18, 2025

- Posted by: Jouré Rustemeyer

- Category: Executive Function Neurodivergent

1. What Is Decision Fatigue?

Decision fatigue describes the decline in quality of decisions following prolonged or repeated choice-making. It stems from the broader concept of ego depletion—where self-control and executive function draw on a limited pool of mental resources. When these resources are exhausted, individuals experience impaired judgment, greater impulsivity, and a tendency to default to habitual responses.

2. How It Happens (Causes)

Decision fatigue arises from several interacting factors:

- 1. Repeated acts of self-regulation: Each decision, especially those involving inhibition or choice, draws on self-control. Over time, this depletes available cognitive resources.

- 2. Cognitive load and complexity: Navigating complex decisions—or multitasking—places greater demand on working memory and executive processes .

- 3. Psychobiological signalling: The brain evaluates the effort-versus-reward of continuing. When perceived effort exceeds expected benefit, subjective fatigue sets in, even without physical energy loss (sciencedirect.com).

- 4. Multifactorial triggers: Factors including sleep deprivation, sensory input, emotional distress, and poor nutrition all contribute to cognitive resource depletion .

3. What Decision Fatigue Looks Like (Symptoms)

Manifestations include:

3.1 Avoidance of Trade-offs

Symptom: As cognitive energy declines, individuals may avoid making decisions that require weighing options, comparing pros and cons, or imagining hypothetical outcomes.

Examples:

- A parent scrolling endlessly through meal delivery apps but eventually ordering the same default food as last time, just to avoid the mental strain of choosing.

- A therapist putting off updating client records because deciding where to start feels overwhelming.

- A student staring at several assignments but avoiding all of them because they can’t decide which is most urgent or most manageable.

3.2 Increased Impulsivity or Conservatism

Symptom: When self-control is depleted, people either make snap, impulsive decisions (e.g., buying things they don’t need) or freeze and stick to the safest option—even if it’s suboptimal.

Examples:

- Impulsively agreeing to an additional work task despite an already full schedule, simply to end the conversation.

- Saying “no” to all invitations or opportunities, not from preference, but to avoid having to decide.

- Clicking “Accept All Cookies” on a privacy settings pop-up without reading, just to move on quickly.

3.3 Cognitive Inefficiencies

Symptom: A drop in decision quality and task completion efficiency. Thoughts become slower, fragmented, or repetitive. There is difficulty switching between tasks or integrating new information.

Examples:

- Re-reading the same paragraph multiple times and still not absorbing the content.

- Opening a browser tab to complete a task but then forgetting what you were supposed to do.

- Writing and rewriting the same email because it never “feels right,” even though the content is clear.

3.4 Emotional Dysregulation

Symptom: As cognitive resources decline, emotional self-regulation also weakens. People may become more irritable, anxious, or emotionally sensitive.

Examples:

- Snapping at a colleague over a minor misunderstanding after a long morning of back-to-back meetings.

- Feeling overwhelmed and crying after a seemingly small request, like being asked “What’s for dinner?”

- Experiencing decision paralysis in the supermarket and walking out without buying anything.

4. How This Relates to ADHD, ASD, and Dyslexia

Decision fatigue does not affect everyone equally. Neurodivergent individuals—particularly those with ADHD, autism (ASD), and dyslexia—often experience decision fatigue more intensely and more frequently. This is due to increased cognitive effort required for everyday functioning, differences in executive function development, and, in many cases, heightened sensory sensitivities. While the core symptoms of decision fatigue may appear similar, their root causes and expressions differ significantly across neurodivergent profiles.

4.1 ADHD (Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder)

People with ADHD often experience:

- Reduced working memory: Holding multiple pieces of information in mind (e.g. steps in a task or options to compare) can become effortful very quickly. This overload accelerates decision fatigue.

- Impaired inhibitory control: Making decisions without acting on impulse requires executive effort. Since inhibition is often a challenge in ADHD, fatigue emerges faster from repeated attempts at self-regulation.

- Difficulty with sustained attention: Keeping attention on a task long enough to weigh decisions can lead to premature or incomplete choices.

Sensory Sensitivities in ADHD

Although sensory processing difficulties are more commonly associated with autism, a significant number of people with ADHD also report sensory sensitivities. These can include:

- Auditory sensitivity: Difficulty filtering background noise (e.g. office chatter, ticking clocks), which leads to greater cognitive effort just to focus.

- Tactile defensiveness: Discomfort with clothing textures, tags, or tightness, which can become distracting and draining.

- Light sensitivity or visual overwhelm: Difficulty focusing under harsh lighting or in cluttered environments.

Importantly, ADHD medications (particularly stimulants) can sometimes amplify these sensitivities—especially if dosage is high or if the person is already overwhelmed. Increased alertness may also increase sensory awareness, making ordinary environments feel more intense. This contributes to faster cognitive and emotional burnout, especially in overstimulating settings like classrooms, shopping malls, or open-plan offices.

4.2 Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

In individuals with autism, the causes of decision fatigue are often more cumulative and environmental. Key contributing factors include:

- Need for predictability: Many autistic people find uncertainty distressing. Everyday decisions (like choosing an unfamiliar brand or route) require extra mental rehearsal to manage this uncertainty, leading to quicker cognitive exhaustion.

- Social decision-making: Understanding implied expectations, reading nonverbal cues, and navigating social scripts require continuous decoding and choice-making, which draws heavily on executive function and working memory.

- Cognitive rigidity: Decision-making that involves flexibility (e.g. adapting to last-minute changes) can be overwhelming when the individual is already managing internal rigidity and external unpredictability.

Sensory Sensitivities in Autism

Sensory processing differences are a core feature of ASD and may include:

- Hypersensitivity (e.g. to noise, smell, textures) that creates constant low-level stress and distraction.

- Hyposensitivity in some modalities, requiring greater environmental scanning or physical stimulation, adding to cognitive load.

- Sensory avoidance or sensory seeking behaviours that add another layer of effort to daily decisions—such as choosing quiet seating, avoiding crowds, or regulating clothing preferences.

For autistic individuals, sensory management is often as cognitively taxing as decision-making itself, and the two compound each other. For example, choosing what to wear may not just be about fashion or weather—it may involve a complex calculation about how fabrics feel, how the lighting will affect perception, or whether noise levels will allow the use of noise-cancelling headphones.

4.3 Dyslexia

Dyslexia primarily affects reading and language-based processing, but its impact on decision fatigue should not be underestimated.

- Slower or effortful decoding: Making decisions that involve written text (e.g. reading menus, instruction manuals, contracts) can be far more tiring and time-consuming.

- Processing delays: Difficulty rapidly retrieving word meanings or auditory instructions can lead to decision paralysis, especially under pressure.

- Compensatory strategies: People with dyslexia often develop workarounds that are mentally effortful (e.g. re-reading, scanning for context clues, using speech-to-text), which raises the baseline cognitive load.

Emotional and Social Load

In many cases, people with dyslexia report feeling judged when they need extra time to make decisions or read something carefully. This self-consciousness increases cognitive pressure and may lead to avoidance or default decisions—core signs of decision fatigue.

All three conditions involve heightened executive demand, and when paired with overstimulation, reduced predictability, or performance pressure, decision fatigue becomes not just likely—but a frequent lived experience.

5. How Decision Fatigue Links to Executive Function Skills

Executive function (EF) refers to a set of higher-order cognitive processes that allow us to plan, organise, prioritise, initiate tasks, shift between ideas, inhibit impulses, and regulate emotions. These functions are largely governed by the prefrontal cortex and play a central role in decision-making. When executive resources are stretched or depleted—whether by complex demands or accumulated stress—the brain experiences decision fatigue. This decline isn’t simply about being tired; it’s a systemic reduction in mental clarity, control, and flexibility.

5.1 Executive Functions Involved in Decision-Making

The following EF domains are particularly involved in decision-making and thus directly impacted by decision fatigue:

- Working memory: Holding and manipulating information in mind to compare choices or recall prior outcomes.

- Cognitive flexibility: Shifting between perspectives or strategies when making choices in uncertain or changing environments.

- Inhibitory control: Resisting impulses and emotional reactions to make reasoned decisions.

- Planning and organisation: Setting goals, anticipating outcomes, and sequencing tasks toward a future choice.

- Emotional regulation: Modulating anxiety or frustration that may influence decisions under pressure.

When a person is experiencing decision fatigue, each of these systems may become compromised. For example, they may:

- Forget important context for a decision (working memory failure),

- Struggle to think of alternatives (loss of cognitive flexibility),

- React emotionally or impulsively (inhibitory failure),

- Avoid planning (reduced foresight), or

- Shut down entirely in the face of multiple options (executive overload).

In neurodivergent individuals—particularly those with ADHD, autism, and dyslexia—these executive functions may already operate differently, creating a lower baseline capacity for sustained decision-making. Thus, it takes less cumulative stress or cognitive load for decision fatigue to set in.

5.2 Neurobiological Underpinnings

Neuroscientific studies (e.g., Baumeister et al., 2007; McEwen & Morrison, 2013) have shown that the prefrontal cortex (PFC)—the seat of executive function—is especially sensitive to mental effort and stress. When this area is depleted (either due to repeated decisions, emotional labour, or sensory stress), the brain reverts to more automatic systems, such as the limbic system and habitual patterns. This explains why people experiencing decision fatigue may:

- Default to habitual choices (even when they’re suboptimal),

- Rely on heuristics (mental shortcuts),

- Make snap decisions without evaluation, or

- Avoid decisions entirely.

In people with ADHD, this shift can happen much faster, due to inherent differences in dopaminergic signalling in the PFC. This means less resilience to sustained mental effort and a greater tendency to “shut down” when overloaded with decisions.

5.3 Functional Consequences in Everyday Life

When executive function systems are taxed—by prolonged decision-making, multitasking, or managing social demands—the symptoms of decision fatigue become visible in multiple domains:

- In the workplace: Missed deadlines, choosing easier tasks over important ones, impulsive email responses, or avoidance of complex projects.

- At home: Decision paralysis around meals, breakdowns in household routines, or difficulty initiating transitions (e.g., from screen time to bedtime).

- Socially: Withdrawing from conversations that require emotional or cognitive engagement, relying on stock phrases, or ghosting rather than navigating complex discussions.

- In therapy or education: Difficulty following through on plans, resisting new strategies, or showing emotional reactivity when choices are required.

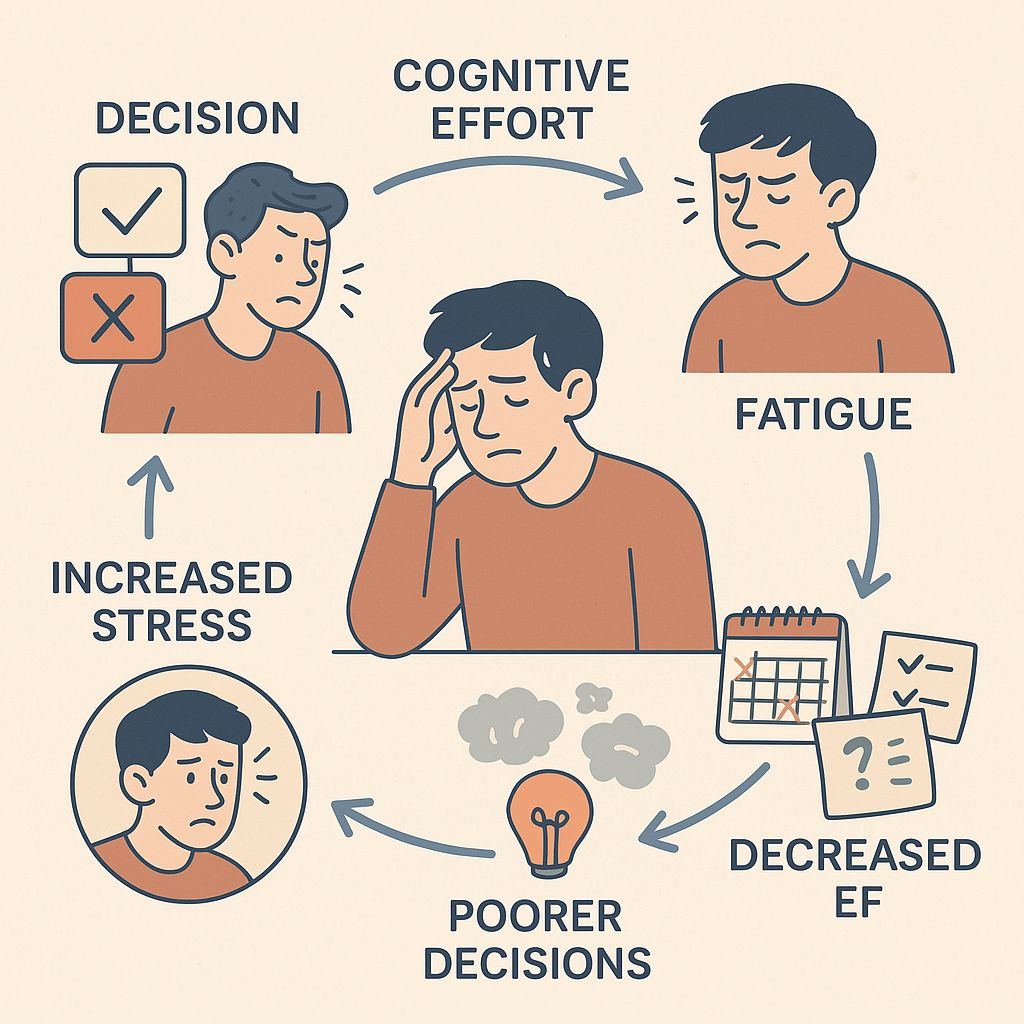

5.4 Compounding Feedback Loop

Crucially, decision fatigue can further impair executive function in a compounding cycle:

Decision → Cognitive effort → Fatigue → Decreased EF → Poorer decisions → Increased stress → Further EF decline

This downward spiral is particularly pronounced in neurodivergent individuals, who are more likely to:

- Experience EF challenges even in rested states,

- Be exposed to environments that overtax their decision-making systems (e.g., open-plan classrooms, noisy clinics, rigid social scripts), and

- Face higher rates of burnout due to sensory overload and masking (especially in autistic individuals and women with late ADHD diagnoses).

In short, decision fatigue is both a symptom and a stressor on executive function. It emerges from repeated or high-stakes choices and, once present, further depletes the very skills required for resilience, planning, and emotional balance.

One lesser known example of refers to a well‑documented study on the so‑called “hungry judge effect”, which illustrates how decision fatigue impacts real-world judgments:

- Researchers analysed over 1,000 Israeli parole decisions in 2011. They found that approval rates began around 65% at the start of a session, then declined steadily to nearly zero just before breaks, before rebounding to about 65% after a rest pnas.org+10en.wikipedia.org+10reddit.com+10.

- The authors concluded that as judges grew mentally fatigued, they increasingly opted for the default (denial) option, which was cognitively easier nature.com+3wired.com+3theguardian.com+3.

- This dramatic pattern—declining leniency followed by replenished judgment post-break—strongly suggests that cognitive depletion, not case content, drove their decisions .

This real-world finding powerfully illustrates the cycle of decision fatigue:

Decision → Cognitive effort → Fatigue → Default decisions → Stress

6. Glucose, Beliefs, and Subjective Fatigue

While early studies implied low glucose as the culprit behind decision fatigue, robust peer-reviewed work now indicates that subjective perceptions of mental resources—“mental fatigue”—play a dominant role.

6.1 Perceived Effort and Internal Signalling

- Modern models propose that the brain continuously monitors effort and adjusts performance based on cost–benefit evaluations. When mental costs outpace anticipated benefits, subjective fatigue is triggered—even if no actual energy deficit exists (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

- Neural circuits in the anterior cingulate and insula generate this internal signal, functioning independently of glucose depletion (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

6.2 Placebo, Glucose, and Willpower Beliefs

- Meta-analyses (e.g., Hagger et al., 2016) found no consistent link between declining blood glucose and self-control performance; when glucose mouth rinse alone restored performance, it suggested a motivational, not metabolic, effect (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

- Foundational studies by Job, Walton & Dweck (2013) demonstrated that only individuals who view willpower as a limited resource show performance improvement after actual glucose consumption. Those with a nonlimited mindset performed well regardless—and interestingly, the effect was seen even when participants merely believed they had consumed sugar (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

- The evidence implies that perceived resource availability—via belief or a sugar ritual—is sufficient to sustain decision-making more than real physiological change .

6.3 Summary

Today’s peer-reviewed consensus emphasizes that:

- Actual glucose levels have a marginal causal role in decision fatigue.

- Subjective signalling of cognitive effort—not physical energy pools—is the primary driver.

- Beliefs and motivational frameworks profoundly influence whether mental resources feel exhausted or renewable.

Interventions that address mindset, rest, and context can therefore alleviate fatigue even without altering metabolic state.

7. What Can Be Done to Prevent Decision Fatigue?

Preventing decision fatigue requires reducing the cumulative cognitive load placed on a person’s executive function system across the day. For neurodivergent individuals—particularly those with ADHD, autism, or dyslexia—this means not only managing the number of decisions made but also reducing the intensity and sensory/emotional load of those decisions.

Preventive strategies fall into three key categories:

7.1 Reduce the Number of Decisions

One of the simplest and most effective strategies is to reduce the volume of decisions required each day.

Key strategies include:

- Precommitment and automation

Establish habits, routines, or defaults so that certain choices are pre-made. For example:- Wearing the same style of clothing each day (e.g., Steve Jobs’ turtlenecks) to eliminate outfit decisions.

- Preparing a weekly meal plan in advance to avoid last-minute food choices.

- Using automatic bill payments or calendar reminders to reduce admin-related decisions.

- Environmental structuring

Create an environment that removes unnecessary options. For instance:- Keep only a few visible snacks to avoid constant food decision-making.

- Minimise visual clutter to reduce overstimulation and task-switching.

These techniques are supported by research showing that people who reduce their daily decisions—especially minor, repeated ones—preserve cognitive energy for more meaningful, goal-directed thinking (Vohs et al., 2008; Muraven & Baumeister, 2000).

7.2 Frontload High-Energy Tasks

The time of day plays a critical role in cognitive performance. The brain’s capacity for effortful thinking is highest earlier in the day, especially after rest and nutrition. For neurodivergent individuals, this window may be even shorter.

Suggestions:

- Schedule demanding tasks in the morning, before fatigue accumulates.

- Avoid decision-heavy meetings or sessions late in the day.

- Use predictable routines for the afternoon or evening (when EF is lowest).

This principle aligns with chronopsychological research indicating that effortful self-control and complex cognition decrease as the day progresses (Baumeister et al., 1998).

7.3 Use Decision Frameworks

Decision fatigue often arises not just from making decisions, but from the emotional labour of weighing options. Using simplified frameworks or heuristics can help.

Examples:

- “If/Then” rules: “If I receive an email from a client after 6pm, then I will respond the next morning.” This removes internal debate.

- Rule-based prioritising: Choose tasks based on a single dimension (e.g., time-sensitive first) rather than multi-factor analysis.

- The 2-minute rule: If something takes less than 2 minutes, do it immediately. If it takes longer, schedule it.

For neurodivergent people, this kind of external structure supports cognitive offloading—removing the burden of internal regulation and instead relying on consistent cues.

7.4 Protect and Replenish Cognitive Resources

Preventing decision fatigue also involves actively supporting the brain’s energy systems. This includes both physiological and emotional supports:

- Rest and breaks: Regular short breaks—especially those that remove cognitive and sensory input (like walking outside or lying down in silence)—can restore prefrontal cortex function.

- Minimising sensory input: For those with sensory sensitivities (especially in ADHD or ASD), managing lighting, noise, and texture can prevent the early onset of cognitive overload and burnout.

- Emotional co-regulation: Access to calm, validating relationships can reduce the emotional drain of decision-making—particularly when choices involve social risk or ambiguity (common triggers for autistic individuals and those with rejection sensitivity).

7.5 Psychological Flexibility and Self-Compassion

Research also shows that people who hold rigid expectations of productivity or control are more susceptible to decision fatigue, especially if they see indecision as a personal failure (Inzlicht & Berkman, 2015). For neurodivergent individuals who have internalised stigma about their capacity, this can be especially damaging.

To protect against this:

- Practice self-compassion: Acknowledge that fatigue, avoidance, or “shutdowns” are neurological responses—not laziness or weakness.

- Develop flexibility around success: Define progress in adaptive, not perfectionist, terms. E.g., “I prepared one email draft today” may be more realistic and protective than aiming to complete a full proposal during a day of fatigue.

In summary, preventing decision fatigue is not just about making fewer choices—it’s about:

- Structuring your day,

- Supporting your brain’s resources,

- Using predictable tools and routines, and

- Responding with compassion to natural cognitive limits.

When these practices are integrated into daily life, particularly in environments where neurodivergence is understood and supported, the likelihood of decision fatigue drops significantly—and functional capacity improves in a measurable, sustainable way.

8. Practical Help to Avoid Decision Fatigue

(Including Time Blocking vs. Task Batching for Neurodivergent Minds)

Even when decision fatigue cannot be fully prevented, there are practical ways to manage mental load and create sustainable work rhythms. Two commonly used productivity strategies—time blocking and task batching—can help preserve executive function and reduce daily decision pressure. However, they work differently, and neurodivergent individuals may find one more effective than the other depending on their needs, context, and natural cognitive rhythms.

8.1 What is Time Blocking?

Time blocking is a planning method where each segment of your day is pre-allocated for a specific task or activity. It is typically visualised as a calendar with defined blocks (e.g., 9:00–10:00 = emails, 10:00–11:30 = deep work, 12:00–13:00 = lunch).

Benefits:

- Reduces the number of decisions about “what to do next.”

- Helps ensure deep work gets dedicated time.

- Can support prioritisation if blocks are pre-planned the day before.

Challenges for neurodivergent individuals:

- Low task switching tolerance: People with ADHD or autism may find it hard to stop an enjoyable task simply because the time is “up.”

- Executive load: Strict adherence requires significant inhibition, transition skills, and internal regulation.

- Rigidity: For autistic individuals, unexpected disruptions can create anxiety or disorganisation, especially when plans are too prescriptive.

- Shame spiral: Failing to follow the blocked schedule (due to executive dysfunction, fatigue, or sensory overload) may lead to frustration or self-criticism.

While time blocking can work well for some—particularly when external structure and low-stimulus environments are in place—it can backfire when enforced too rigidly in neurodivergent contexts.

8.2 What is Task Batching?

Task batching involves grouping similar tasks and doing them together in a flexible window, rather than according to a rigid time schedule. For instance, instead of answering emails at 9:00 sharp, you might batch all email replies into one focused session at any point during the afternoon. Unlike time blocking, batching is focused on the type of task, not the time of day.

Examples:

- A) Batch all admin tasks (emails, invoices, calendar bookings) together.

- B) Batch all creative work (writing, course design, research) together.

- C) Batch all phone calls or meetings into one part of the week.

Benefits:

- Reduces context switching, which is a major source of decision fatigue and executive drain.

- Offers flexibility: you can complete the batch whenever energy levels or sensory capacity allow.

- Makes transitions smoother: grouping similar mental demands avoids the “gear shift” that neurodivergent brains may struggle with.

- Builds flow: People with ADHD often enter hyperfocus more easily when they stay in a similar cognitive zone without interruption.

Why task batching is often better suited for neurodivergent people:

- Allows for energy-based planning, which respects fluctuating executive capacity throughout the day.

- Minimises the emotional distress that can come with unpredictable demands or rigidity.

- Works well with interest-based nervous systems (especially in ADHD), since batching can be built around preferred or engaging activities.

- Reduces decision-making moments: instead of deciding every hour “what’s next?”, you simply return to the current batch until it’s complete.

8.3 Real-Life Examples

Let’s take three common neurodivergent profiles and see how batching might support them more effectively than blocking:

ADHD

Problem: Difficulty transitioning between tasks, poor time perception, and resistance to boring tasks.

Batching Benefit: By grouping mundane tasks (e.g. all house chores or email replies) into a single burst of effort, the person can use momentum, body doubling, or rewards more effectively without needing to track time closely.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Problem: Sensory overload, need for predictability, and intolerance of unexpected transitions.

Batching Benefit: Sensory-heavy tasks (e.g. social interaction or shopping) can be batched on days when sensory input is easier to manage, leaving low-input days for recovery and focused thinking. This reduces emotional decision-making and preserves resources.

Dyslexia

Problem: Reading-heavy or language-based tasks are cognitively and emotionally demanding.

Batching Benefit: Scheduling all reading tasks together allows use of compensatory strategies (like text-to-speech or large fonts) in one go, reducing the need to constantly re-prepare or switch formats.

8.4 Combining Both Approaches

Some people may find that a hybrid approach works best:

- Use task batching to organise the types of tasks in a flexible way.

- Use light time blocking only for high-priority appointments or for containing specific tasks (e.g. “creative time before 2pm”).

- Let energy levels, sensory states, and emotional wellbeing guide the timing of each batch.

This way, structure is present, but not imposed—respecting the unique rhythm of the neurodivergent brain while still reducing executive overload.

8.5 Final Tips for Practical Success

- Use visual cues like sticky notes, Kanban boards, or colour-coded lists to mark batches.

- Build buffer zones between activities, especially when switching sensory or emotional gears.

- Reward completion of batches with preferred activities to reinforce engagement.

- Regularly audit your decisions: Which choices are costing too much energy? Can they be automated, delegated, or removed?

In summary, while both time blocking and task batching aim to reduce cognitive overload, task batching offers a more adaptable, resource-sensitive model for people with ADHD, autism, and dyslexia. It supports autonomy, reduces transitions, and allows for the realities of fluctuating energy and executive function—key contributors to preventing decision fatigue in neurodivergent lives.